NOTE (Update): This article should be read as a follow-on to "Why is this?" The question at hand is whether food costs are actually dominated by petroleum costs.

So far we have seen a wide variety of opinions proffered: one is that the coincident recent price spikes are indeed coincidental.

That all commodities move together to some extent remains plausible from where I am sitting. Does anyone have some input on that?

Here are real commodity prices and real oil prices over a longer time span. There is some question as to when we are looking at paleo-agriculture. Certainly oil prices in 1870 are irrelevant.

I had a harder time finding traded food prices, but this one comes from Phil Trans Roy Soc, so I think we can take it as reasonably authoritative, but it predates the recent glitch

It's crucial to note that vulnerability of the poorest states to food prices is relatively new. Before urbanization of the third world, bulk food was not a market commodity for poor people; communities grew their own staples. So taking this history too far back doesn't really speak to food security in the sense of the organization of global society.

The results, taking these particular plots at face value, are equivocal. We see a very close match between oil spikes and food spikes since 1960, but there is a price spike which clearly has some other cause around 1950.

The food price chart is from Jeremy Grantham, with a hat tip to Keith Kloor. I found a number of similar oil price charts via google images; this representative one is via "Supply Chain Digest".

It looks to me like there is plenty of circumstantial evidence that the current price rise is tied to the oil price rise. The alternative theories:

- Direct forcing by oil prices

- Speculation yielding common pressures across commodities

- Increased middle classes in China bidding prices up for animal feed over human use

- Increased biofuel demand

- Crop damage due to widespread climate disruption

I had been inclined to #3 as the primary forcing, reinforced by #5. But the synchrony of the oil and food prices is striking enough to pull my attentions back to the first two possibilities.

It matters a great deal, I think, which causes are at work. I had been one of those less concerned with peak oil, but if the first possibility holds we really are in a bad way.

Again, we have to separate out the oil price and the energy price. energy prices have been stable except for petroleum, which is mostly about fueling mobile heavy equipment. Certainly mobile heavy equipment is important to modern farming, but I would not have anticipated that the fuel costs would figure so prominently. I can't think of any other basis for the first.

If it's just speculation, we have an entirely different sort of problem, which amounts purely to a regulatory issue and not to a real-world physical problem at all. That would hardly be unprecedented, but if that's true, why is this not a prominent issue?

Color me confused.

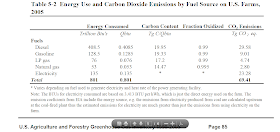

Update: Some recent numbers for agricultural fuel consumption in the US.

From here: US farming in 2005 was worth 127 billion dollars.

From here, a gallon of gasoline is 114 K Btu. Treating diesel and gasoline as roughly equivalent, we have 637 trillion/114 thousand = 5.6 billion gallons of liquid fuel. Even at $4 per gallon this amounts to only 1/6 the total price. So at first pass the food price is overreacting to the fuel price by a factor of about 4.

Possible confounds: meat double counting: a good fraction of agriculture is for animal feed rather than directly for humans. This will increase the fuel intensity dramatically for that sector. Non-food components, especially forestry, accounts for a significant fraction of GDP and is low energy use. Luxury foods, perhaps not counted in the FAO index, which will produce a high GDP per unit of energy because they are labor-intensive and/or high-profit.

So, we have a dollar's worth of food containing at least 18 cents worth of liquid fuel at present prices, only 9 cents at 2005 prices, at the moment the farmer sells to the distributor. This does NOT count the energy input into the fertilizer or heavy equipment or other items purchased by the framer.

Update via Rust Never Sleeps in comments:

More in Smil 2008 Energy in Nature and Society: General Energetics of Complex Systems.

Very much the sort of thing I was looking for, thanks.

I still don't understand why food prices should be as sensitive to gasoline prices as the last few years would seem to indicate. I presume the basket used by the FAO is not heavily processed, since we are mostly interested in what food for the poorest people costs. It seems everything besides mobile farm equipment and trucking can easily have substitute energy sources.

But if farmers and truckers have to compete with the whole market for tractor fuel, prices should indeed go up, if not quite as steeply as we see. Obviously, demand for grain is inelastic, and will perversely increase as the price goes up (and demand for meat goes down). Ultimately, food is what we need and everything else is what we want. That food should be cheap enough that we throw a good fraction away is bizarre...

From here, a gallon of gasoline is 114 K Btu. Treating diesel and gasoline as roughly equivalent, we have 637 trillion/114 thousand = 5.6 billion gallons of liquid fuel. Even at $4 per gallon this amounts to only 1/6 the total price. So at first pass the food price is overreacting to the fuel price by a factor of about 4.

Possible confounds: meat double counting: a good fraction of agriculture is for animal feed rather than directly for humans. This will increase the fuel intensity dramatically for that sector. Non-food components, especially forestry, accounts for a significant fraction of GDP and is low energy use. Luxury foods, perhaps not counted in the FAO index, which will produce a high GDP per unit of energy because they are labor-intensive and/or high-profit.

So, we have a dollar's worth of food containing at least 18 cents worth of liquid fuel at present prices, only 9 cents at 2005 prices, at the moment the farmer sells to the distributor. This does NOT count the energy input into the fertilizer or heavy equipment or other items purchased by the framer.

Update via Rust Never Sleeps in comments:

"The energy costs of common foodstuffs range widely, due to different modes of production (such as intensity of fertilization and pesticide applications, use of rain-fed or irrigated cropping, or manual or mechanized harvesting) and the intensities of subsequent processing. The typical costs of harvested staples are around 0.1toe/t* (*ton of oil equivalent per ton) for wheat, corn and temperate fruit, and at least 0.25 toe/t for rice. Produce grown in large greenhouses is most energy intensive: peppers and tomatoes costs as much as 1 toe/t. Modern fishing has a similarly high fuel cost per kilogram of catch. These rates can be translated into interesting output/input ratios: harvested wheat contains nearly four times as much energy as was used to produce it, but the energy consumed in growing greenhouse tomatoes can be up to fifty times higher than their energy content.

These ratios show the degree to which modern agriculture has become dependent on external energy subsidies: as Howard Odum put it in 1971, we now eat potatoes partly made of oil. But they cannot simplistically be interpreted as indicators of energy efficiency; we do not eat tomatoes just for their energy, but for their taste, and vitamin C and lycopene content, and we cannot (unlike some bacteria) eat diesel fuel. Moreover, in all affluent countries, food's total energy cost is dominated by processing, packaging, long-distance transport (often with cooling or refrigeration), retail, shopping trips, refrigeration, cooking and washing of dishes - at least doubling, and in many cases tripling or quadrupling, the energy costs of agricultural production."(Smil, Energy, 2006. pg. 152)

More in Smil 2008 Energy in Nature and Society: General Energetics of Complex Systems.

Very much the sort of thing I was looking for, thanks.

I still don't understand why food prices should be as sensitive to gasoline prices as the last few years would seem to indicate. I presume the basket used by the FAO is not heavily processed, since we are mostly interested in what food for the poorest people costs. It seems everything besides mobile farm equipment and trucking can easily have substitute energy sources.

But if farmers and truckers have to compete with the whole market for tractor fuel, prices should indeed go up, if not quite as steeply as we see. Obviously, demand for grain is inelastic, and will perversely increase as the price goes up (and demand for meat goes down). Ultimately, food is what we need and everything else is what we want. That food should be cheap enough that we throw a good fraction away is bizarre...

> Before urbanization of the third world, bulk food was not a market commodity for poor people; communities grew their own staples

ReplyDeleteAnd therefore starved when crops failed. Whereas now they just sell their furniture?

> that the coincident recent price spikes are indeed coincidental.

ReplyDeleteDid anyone suggest that? I certainly don't believe it. It seems more likely that they are both driven by increasing demand / wealth.

To your first comment, it depends on the country. Egypt, notably, depends on foreign aid denominated in currency, not in bushels and pecks.

ReplyDeleteBut indeed, the population was held to levels supportable in bad crop years. When food became cheap, it wasn't. Now that food is expensive again, what we have may end up being a huge bait and switch.

To your second comment, that is what I believed recently (Chinese demand for meat, primarily, driving up demand for animal feed which competes with the lowest grades of cereal for human consumption, which starves Egypt and Haiti).

ReplyDeleteBut the high volatility in oil prices has many other causes which are independent of the relatively slower increase in demand. That the bumps in food prices match the bumps in oil prices so closely causes me to question my prior belief in that analysis.

MT: "But the synchrony of the oil and food prices is striking enough to pull my attentions back to the first two possibilities [forcing by oil and speculation]."

ReplyDeleteIn your post "Why is this" the graph clearly shows oil prices lagging food prices in the run-up phase of the 2007 and 2009 spikes. If oil prices were driving food prices, you would expect the lag to be, if anything, the other way round.

It's true that speculation can distort prices, especially over the short term. For commodities like oil, which, once produced, are expensive to store, longer term price trends (which are the ones we should be mostly interested in) can only be driven by fundamentals of supply and demand. It's a bit like blaming ENSO for global warming trends.

I don't doubt that high oil prices will raise the cost of food, eventually. It's just more likely that other factors, the economic and physical weather, dominate in the short term.

Increased irrigation

ReplyDeleteIncreased refrigeration needs for perishables

Increased meat consumption

Increased fertilizer and pesticide use

Andy, I don't find lag/lead arguments on the margins very compelling; the eye wanders to features that aren't important. The important point is that increases and decreases are mostly synchronous.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, if you are seriously suggesting that food prices force oil prices, you have got a lot of 'splainin' to do.

Jim, "increased refrigeration needs" is surely tiny on this time scale especially, and not relevant to oil.

ReplyDeleteMeat consumption, yes, that's what I previously thought, but that doesn't account for the high frequency variations.

What I am trying to account for is why petroleum price (NOT energy price) appears tightly coupled to food price on a seasonal time scale.

Michael: "Anyway, if you are seriously suggesting that food prices force oil prices, you have got a lot of 'splainin' to do."

ReplyDeleteThe last paragraph of my previous post actually said the exact opposite. I just don't believe that there's enough evidence to assert that short-term spikes in the price of oil will cause immediate big fluctuations in the price of food. Sure, green beans flown from Kenya to London will get a bit more expensive right away.

One factor where there may be some oil-food linkage is in sugar prices. Sugar prices ran up up more quickly in 2010 than any other food category.

http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foodpricesindex/en/

I guess it's possible that this could be linked to Brazilian ethanol production from sugar. As the oil price goes up, the Brazilians might divert more cane to fuels than food. But, that's just speculation on my part.

Seasonal? Then why do all the graphs deal with centennial scales. Color me confused.

ReplyDeleteAll perishable food, which is constantly increasing in amount, is kept either cooled or frozen during transport. That's petroleum that's both transporting it and keeping it cold. As I said before, it's just one of a number of factors that add up. Most of them are in the production process however.

The centennial graphs are in response to those on the previous thread who suggested that the recent synchrony in spikes is coincidental; see "Why is This?"

ReplyDeleteThe mystery is whether petroleum dominates the food price index as it appears to, and if so, why.

I think most of the answers still seem to rely on random coincidence; I suppose it's possible. The fact is that there must be SOME influence of oil on food prices but the latest evidence makes it look surprisingly large. So that's what I'm trying to figure out. How big is the influence on production costs really, and does it account for the scale of the recent food price rise.

Because if it does, it seems that we would have an even more immediate and urgent problem than climate change. In other words, the linked diagram is causing me to question my belief that peak oil is a relatively minor problem.

Around here the farmers (if we can still call them that) grow wheat two years followed by one year of dry peas or lentils. Increasingly this is all no-till reducing the number of passes over the fields to just five (I think). That all requires diesel. During and after harvest the wheat is trucked down to the elevators at the barge terminal and at some later time the farmer sells his grain against the spot price. There are variations, but the point is that production costs do not determine the price the farmer obtains for his crop.

ReplyDeleteBoth wheat and the dry legumes are long lasting commodities. However, the farmer's sale price is determined to a great extent by how well other wheat producing regions of the world have fared in the same crop year. For example, with last summer's events closing exports from Russia, the Ukraine and Kazakstan, the local farmers sold for the highest prices ever (not accounting for inflation). This year's yeld looks to be about as equally large as last year's but the world's wheat production elsewhere looks to be rather poor. So I expect the prices received for the 2011 crop to be even higher.

Briefly, local production costs do not determine food crop prices for these staples.

David, yes, that makes sense, especially for the main internationally traded commodities. So, not to be boring or anything, why is the petroleum signal instantly visible?

ReplyDelete"but there is a [food] price spike which clearly has some other cause around 1950"

ReplyDeleteLooking at that, I'd say it's a double spike that starts around the end of WWII. I can think of a few reasons why food prices would have spiked around then.

Michael Tobis --- I don't know why. I'm not an economist. I earlier suggested checking Granger causality for the two time series (starting around 1955--1960). But if it obvious to the eye that food prices lead oil prices, it is clear how the G-causality will go.

ReplyDeleteSo you can color me confused as well.

The Royal Society paper where Michael got his third graph from is worth reading.

ReplyDeletehttp://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/365/1554/3007.full.pdf

The author argues that the fall in food prices from about 1960 is due mostly to globalisation. Any future linkage between oil prices and food is seen as due to high oil prices driving biofuel production at the expense of food. Peak Oil is not a problem (in the author's view) but there are many other future wild cards such as climate change, water markets, international trade policies and the role of transgenic crops.

In other words, there are many factors that drive the oil-food price relationship.

Here's a link to the Royal Society paper that works, I hope

ReplyDeleteDavid, that's a fairly restricted circumstance you're talking about there. A sudden supply drop that big will increase the price for that crop. But we're talking about the commonplace situation over a whole huge range of crops and food products (or at least I thought we were). Energy prices have a definite impact on food prices overall. This is not any kind of news.

ReplyDeleteThe synchronized drop in commodity prices this past week suggests that speculation is the dominant factor in the recent price spike, and is presumably coordinated because the supply of close-to-zero-interest money drives speculation in anything it can simultaneously.

ReplyDeleteI've been reading Keynes' "General Theory" (1935) and ran across a recommendation in Ch. 12, Sec. VI that addresses exactly this issue - something the US has *never* acted on. Perhaps now would be a good time to start?

"It is usually agreed that casinos should, in the public interest, be inaccessible and expensive. And perhaps the same is true of Stock Exchanges. [...] The introduction of a substantial Government transfer tax on all transactions might prove the most serviceable reform available, with a view to mitigating the predominance of speculation over enterprise in the United States."

Why are we taxed when we purchase food and oil, but speculators see no taxes at all when they trade it and drive up prices for their own profit? It's way past time for a financial transactions tax.

Arthur, that it is less counter to my intuition about food costs than the other ideas so far.

ReplyDeleteBut this is on the time scales where I believe economists, and especially Krugman. And Krugman isn't buying it.

Quoth he: "OK, how can speculation affect this picture? The answer is, it has to work through accumulation of inventories — physical inventories. If high futures prices induce increased storage, this reduces the quantity available to consumers, and it can raise the price. ... But for food, it’s just not happening: stocks are low and falling. ... remember, every purchase of a futures contract is also a sale — there’s someone on the other side. And neither the purchase nor the sale changes the physical quantity of the commodity available to the market.

So if and when I see signs that speculation is really driving up prices, I’ll say so. But the signature just isn’t there right now"

Jim Bouldin --- I respectfully disagree: energy costs are a part of production costs; if farmers cannot obtain high enough prices to cover those costs they go out of business (that has happened more than once around here); the prices that farmers receive depend entirely on the demand for their crops, which does not appear to me to be driven by the price of petroleum. I should rather lay the correlation, with food prices leading oil prices, to something else in the global economy, such as too much money.

ReplyDeleteYeah, I read that from Krugman at the time - and he's right that driving prices up via speculation requires moving some of the supply from the present to the future, ie. storage. Though the time-frames can get a little complex (you can speculate on prices several months down the road, and buy and sell on that basis several times before the due date so there's no delivery of anything involved).

ReplyDeleteBut I'm also not sure he has the data necessary to prove his statement that commodities are not accumulating somewhere. Goldman Sachs and others are said to have rented oil tankers to just sit somewhere full of oil waiting for the right price. Is that information reported publicly in "inventories"? I'm not sure.

Grains and other storable crops are indeed stored. People want to eat every day and (other than rice) there is only one crop per year. There are many players in grain markets. While Cargill is big, maybe the biggest, some farmers have some storage themselves as well as the elevator storage. I've never heard of a grain vessel being loaded and then just sitting but that might happen as well.

ReplyDeleteCBOT certainly has grain trading between actual consumers, such as bakeries and pure traders, i.e., speculators. That form of trading in what used to be called corn (small grains) has been going on for centuries. It seems to work, especially when the world has greater reserves than now. One might care to read what Lester Brown has to say about the current (this century) serious lack of reserves.

This is informative. It seems quite sufficent to knock prices for a loop absent speculation or oil price changes.

ReplyDeleteI have a poor understanding of how futures markets work, but it seems to me that real disruptions to production will drive real price fluctuations, and in turn some of the participants in the market are bound to clean up, and if so it's a matter of the dog wagging the tail.

Thanks, Steve. Excellent link.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you're sticking around despite my flaws.

http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foodpricesindex/en/

ReplyDeleteUN world food price index

FYI Michael, what really gets to me is serial Gish galloping. Tolerating it seems unnecessary.

ReplyDelete1. Cost of production

ReplyDelete2. Cost of processing

3. Cost of moving to market

All of these have energy costs, and price sensitivity occurs on the market. EINAB but he lives with one

"The energy costs of common foodstuffs range widely, due to different modes of production (such as intensity of fertilization and pesticide applications, use of rain-fed or irrigated cropping, or manual or mechanized harvesting) and the intensities of subsequent processing. The typical costs of harvested staples are around 0.1toe/t* (*ton of oil equivalent per ton) for wheat, corn and temperate fruit, and at least 0.25 toe/t for rice. Produce grown in large greenhouses is most energy intensive: peppers and tomatoes costs as much as 1 toe/t. Modern fishing has a similarly high fuel cost per kilogram of catch. These rates can be translated into interesting output/input ratios: harvested wheat contains nearly four times as much energy as was used to produce it, but the energy consumed in growing greenhouse tomatoes can be up to fifty times higher than their energy content.

ReplyDeleteThese ratios show the degree to which modern agriculture has become dependent on external energy subsidies: as Howard Odum put it in 1971, we now eat potatoes partly made of oil. But they cannot simplistically be interpreted as indicators of energy efficiency; we do not eat tomatoes just for their energy, but for their taste, and vitamin C and lycopene content, and we cannot (unlike some bacteria) eat diesel fuel. Moreover, in all affluent countries, food's total energy cost is dominated by processing, packaging, long-distance transport (often with cooling or refrigeration), retail, shopping trips, refrigeration, cooking and washing of dishes - at least doubling, and in many cases tripling or quadrupling, the energy costs of agricultural production."(Smil, Energy, 2006. pg. 152)

More in Smil 2008 Energy in Nature and Society: General Energetics of Complex Systems.

Shorter Michael:

ReplyDeleteOK, that link *entirely disproves* my leading hypothesis that the present food price spike is due to increased oil prices rather than weather-driven crop failure, but that doesn't support the sort of complex analysis I find interesting so let's ignore it and get back to the prior discussion.

Er, WTF?

Actually it came as a big surprise to me that everyone previously commenting seems not to have been aware of what's been going on lately with grain crops globally, in particular with that nasty drought in China (aka the world's largest wheat producer). The article I linked didn't even mention some of the droughts in smaller grain-producing regions, e.g. Iraq-Syria and the Horn of Africa Kenya, probably because they don't contribute much if anything to the world market even in good years (i.e. drought turns them into importers). Pay attention, folks.

My working hypothesis to start was increased demand for meat from the growing middle class, especially in China, and secondarily from biofuels, driving prices up out of reach of poor people. Last year's crop failures did provide a spike independent of oil. But the matching double spikes are too similar to dismiss a connection altogether, so it seems reasonable to re-examine it.

ReplyDeleteNow we have a plethora of causes, none operative until recently, all contributing. That will certainly drive prices up.

And we have impending agricultural decline in large areas dependent on slow-recharge aquifer water (US high plains, Mexico, northern India...)

So, does everybody get to eat? Can rich meat eaters' cattle outbid poor people for grains in a free market? Can anything be done about it if so?

The problem appears quite complicated, and given its importance, as far I can tell so far not settled.

I am not sure on what basis Steve thinks it ought to be settled on his hypothesis. We have lots of evidence in lots of directions.

The evidence I linked relates to the current food price spike only and its (lack of much of a) relationship to the concurrent oil price spike. Long-term influences on food prices are a different matter.

ReplyDeleteWorld Food Situation: FAO Food Price Index has a brief explanation of what is included. Looks like just basics (except for vegatables and fruit) to me

ReplyDeletehttp://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/oil_prices

ReplyDeleteGas (and food) price to drop as oil (and food) joins commodities plunge

Investors finally hit the brakes on oil, gold, silver and food prices. This week's sharp sell-off doesn't mean commodity prices' stunning rise over the last several months is over, but it is good news for anyone planning a road trip this summer.

"Crop damage due to widespread climate disruption"

ReplyDeleteYou left off, drop damage due to widespread inexorably increasing levels of background tropospheric ozone.

Ozone explains not only crop damage but also the decline in trees, and in natural mast for wildlife - such as nuts and seed and fodder - that is stunted in yield and quality.

Sorry, crop not drop.

ReplyDeleteHere's a link to an article about the 2008 food crisis (and ozone levels have only increased since then)

http://feeds.bignewsnetwork.com/index.php?sid=368143

A new research has indicated that rising background levels of ozone in the atmosphere are a likely contributor to the global food crisis, since ozone has been shown to damage plants and reduce yields of important crop, including soybeans and wheat.

The research was conducted by William Manning of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the US.

"Plants are much more sensitive to ozone than people, and a slight increase in exposure can have a large impact on their productivity," said Manning.

"The new ozone standard set by the US EPA in March 2008 is based on protecting human health, and may not be strict enough to protect plants," he added.

According to Manning, emission controls on cars have been successful in reducing short periods of high ozone levels called peaks, but average concentrations of ozone in the atmosphere throughout the year, called the background level, is increasing as polluted air masses from Asia travel to the US and then on to Europe.

Background levels are now between 20 and 45 parts per billion in Europe and the United States, and are expected to increase to between 42 and 84 parts per billion by 2100.

Plants can limit ozone damage for short periods of time by reducing the size of pores on their leaves called stomata. This reduces the uptake of ozone, but also carbon dioxide, which is used as the plants make food through the process of photosynthesis.

Chronic exposure results in reduced photosynthesis, plant growth and yields.

In the long term, leaf injury occurs when the amount of ozone taken in exceeds the leaf's capacity to provide antioxidants to counter its effects.

Manning was recently part of a team of researchers studying how ozone levels in the Yangtze Delta affect the growth of oilseed rape, a member of the cabbage family that produces one-third of the vegetable oil used in China.

By growing the plants in chambers that controlled the ozone environment, the team showed that exposure to elevated ozone reduced the size and weight, or biomass, of the plants by 10 to 20 percent.

Production of seeds and oil was also reduced.

"What was surprising about this research was that plants exposed to ozone levels that peaked in the late afternoon suffered more damage than plants exposed to a steady ozone concentration throughout the day, even though average ozone concentrations were the same for both groups," said Manning.

"This shows that current ozone standards that rely on average concentrations would underestimate crop losses," he added.

A November 2010 article in the NYT headline: World Dangerously Close to Food Crisis

http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/24/world-dangerously-close-to-food-crisis-u-n-says/

"Global grain production will tumble by 63 million metric tons this year, or 2 percent over all, mainly because of weather-related calamities like the Russian heat wave and the floods in Pakistan, the United Nations estimates in its most recent report on the world food supply. The United Nations had previously projected that grain yields would grow 1.2 percent this year."

So, a 2% reduction in global grain production from extreme weather is enough to lead to predictions of a food crisis. Now contrast that 2% loss to this personal correspondence and you will understand why ozone should be on the list of reasons for price increases:

"Dear Gail,

It is generally recognized that 10 to 20% of potential crop yield is lost each year because of ozone...the stunting of plants even by "acceptable" levels of ozone is quite amazing."

- Tom Sharkey, Professor and Chair, Dept. of Biochem. Mol. Biol., Michigan State U...email dated August 2, 2009

David, I see no obvious evidence that food prices lead oil prices over any length of time.

ReplyDeleteMichael: "Obviously, demand for grain is inelastic".

But it isn't; that's actually a big part of what's happened. The rise in oil prices drove a rise in the diversion of corn, sugar cane and soybeans into fuel production (with help from govt. tax breaks, subsidies and whatnot to provide incentives). Since land for production agronomy is relatively fixed over the short term, this helped raise the price of wheat as well.

Yes there was speculation in 2007-08 that helped drive prices up, and yes production limitations can raise prices. The ultimate long term driver however, is fuel cost. However, I'll retract the importance of packaging energy, and to some degree refrigeration, since the FFPI price index you mentioned is relatively unaffected by those.

Jim Bouldin --- I don't see that relationship either, but I thought there was an earlier comment to that effect. As a dispute remains, then somebody should computer G-causality for the two time series.

ReplyDeleteHere's a more detailed article about current grain crop problems. No mention of energy costs.

ReplyDeleteSteve Bloom --- Thanks again for the link.

ReplyDeleteBecause of all that, the wheat producers around here are once again likely to obtain high prices come harvest time. (We've had plenty of precipitation so far this water year.)

Don't cry for Argentina either, David. :)

ReplyDeleteMany other places, not so good.

Here's a link to an mp3 of nine minutes from Thursday's Radio 4 'world at one' on commodities. A panel discusses the issues - some very interesting bits. No agreement on the role of treating commodities as investments, though it's noted pension funds are getting involved. I took away: speculation shouldn't affect the fundamentals, but to the extent that it introduces volality it can cause problems. (Risk is expensive, delays capital investments, etc.)

ReplyDeleteBest line from the end: "frankly, everyone's trying to figure out what's going on."