This post will be updated before and after the AMA event.

Some points for discussion

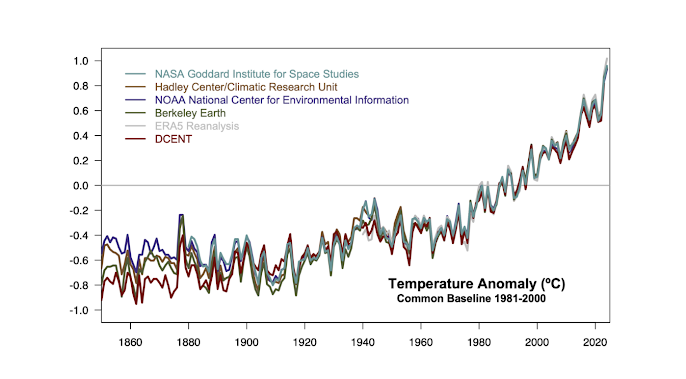

Humans are the dominant force in today’s very rapid climate change.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_surface_temperature

there are a lot of reasons to associate this with CO2

https://keelingcurve.ucsd.edu/

but there are other factors

https://archive.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/figure-spm-2.html

Canada has contributed more than its fair share.

https://decarbonization.visualcapitalist.com/global-co2-emissions-through-time-1950-2022/

Climate always changes but rapid climate change is associated with major extinction events -- massive die-off of insects, plants and animals.

The current rate of global warming and species extinction only has parallels deep in the geological record. More specifically, with the previous five mass extinctions in Earth’s history (Fig. 1). Although those previous extinction events were triggered by distinct phenomena (as far as current theories ago), they seem to elicit similar long-term effects on biodiversity.

incredibly detailed picture of some of these events have come to light. My favourite comparison is with the Permian-Triassic mass extinction at 251.9 million years ago (Ma). Not only this is my current subject of research, but it has also important parallels with current climate change. For instance, both are marked by substantial input of CO2 into the atmosphere (released from hundreds of thousands of years of volcanic activities in what is today Siberia) and potentially aggravated by subsequent release of methane from deep ocean sediments. Perhaps alarmingly, it is estimated that the rate of carbon input into the atmosphere at the end Permian was between 0.42 and 1.52 gigatons of carbon per year (Gt C/yr), whereas current human-induced levels of carbon input are of 31 Gt C/yr! It is not to say that the current warming event is necessarily worse than the one that caused the greatest mass extinction in the history of complex life at 251.9 Ma (this rate would have to sustain for tens or hundreds of thousands of years for that to be true), but only that the current rate of carbon input into the atmosphere is alarmingly high compared to some of the most dramatic events in the geological record.

- Tiago R. Simões https://communities.springernature.com/posts/lessons-from-the-deep-past

Also, when a substantial fraction of species dies, that means a l;ot more species NEARLY died. Most species populations declined severely

Weather everywhere is connected in the global climate system; the physics are well-understood and not controversial.

The weather is the result of energy flows into and out of the earth system. Over the long term these are in balance or the world will warm or cool very quickly. mThey are well understood and mostly well quantified. Best evidence is that there is currently an imbalance of about 1 watt per square meter, which will cause gradual but constant warming until balance is achieved again. But the increase in greenhouse gases continues to disrupt the balance.

The evidence that this view is correct is in the accuracy of weather models and the success of climate models in replicating observed climates. These models are properly called "simulations". The properties of the system emerge from the modeled physics.

A climate model, more specifically a general circulation model (GCM), is a mathematical representation of ocean/atmosphere/land systems based on physical principles (e.g., conservation of momentum, mass, and heat). The physical principles are formulated as a set of equations and these equations are numerically solved on every 3-dimensional grid divided on the globe.

https://cml.jbnu.ac.kr/cml/11846/subview.do

https://hrcm.ceda.ac.uk/blog/plot-of-the-month-mar-2019-10km-global-modelling/

The largest uncertainty in climate prediction is human action -- especially how much fossil fuels we will consume. You ain't seen nothin' yet. Climate change is going to get worse. We can only affect how much worse.

Fossil carbon accumulates. Natural drawdown is very slow. We need to leave a lot of fossil fuel resources untapped.

https://www.carbonbrief.org/explainer-how-the-rise-and-fall-of-co2-levels-influenced-the-ice-ages/

Canada may get off relatively lightly economically, but the natural impact will be enormous. All our forests are at risk.

https://sciencemediacentre.es/en/pep-canadell-we-are-heading-much-warmer-world-15-degrees-warmer

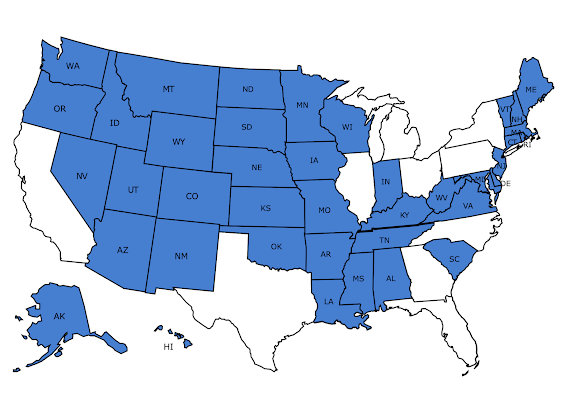

Threats to species in Canada

Increasing importance of climate change and other threats to at-risk species in Canada

any mention of climate change as a threat increased from 12% to 50% in 10 years. Other anthropogenic threats that have increased significantly over time in the paired analysis included introduced species, over-exploitation, and pollution. Our analysis suggests that threats are changing rapidly over time, emphasizing the need to monitor future trends of all threats, including climate change.

https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/er-2020-0032

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-primary-energy